PART I

Into the Fray:

The Flags of the Iron Brigade,

1861-1865

By Howard Michael Madaus

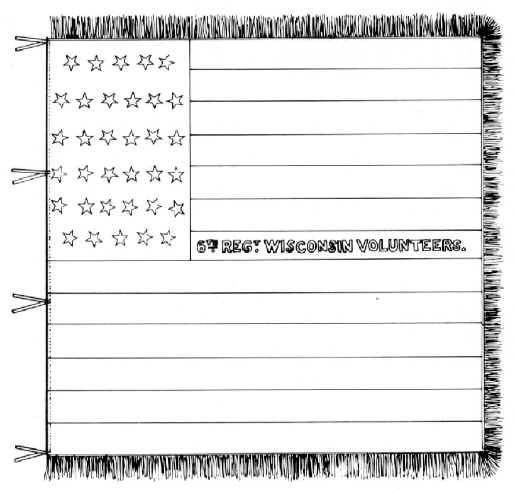

Sixth Wisconsin National Color

... We moved on to battle, and soon the

whole ground shook at the discharges of artillery and infantry. Gainesville, Bull Run,

South Mountain were good respectable battles, but in the intensity and energy of the fight

and the roar of the firearms, they were but skirmishes in comparison to this of

Sharpsburg. . . About twenty stands of colors were captured by us, - two by the 6th Wisc.

The flag of the 6th received four bullets in the flag staff, and some fifteen in the fly,

- that of the 2nd Wisc. three bullets in the staff and more than twenty in the fly. We are

now near the field.

I hope you may never have occasion to see such a sight as it is. (1)

1 Lieut. Frank A. Haskell,

letter September 22, 1862, originally published October 4, 1862, in the Portage Wisconsin

State Register

LIEUTENANT Frank A. Haskell of

Portage, the author of this passage, is better known for his firsthand account of the

battle of Gettysburg. He saw action on some of the bloodiest battlefields of the Civil

War, and he was not given to exaggeration. When he posted this description of the battle

of Antietam (or Sharpsburg) to his brothers and sisters during the autumn of 1862, he had

been serving for four months on the staff of Brigadier General John Gibbon.

The shot-torn flags Haskell made note of - those of the

Sixth Wisconsin and the Second Wisconsin - represented two of the regiments comprising

Gibbon's Brigade, a unit that had won the nickname "Iron Brigade" for its action

at South Mountain, just three days before the appalling slaughter at Antietam. In

succeeding months at Fredericksburg, Chancellorville, and above all on the first day at

Gettysburg - the Midwesterners of Gibbon's Brigade amply justified their claim to being

the bravest of the brave among all the regiments of the Union Army.

The story of the Iron Brigade's march to glory has been told elsewhere. Nevertheless, one

aspect of the brigade's history remains virtually untold: the story of the brigade's

flags. These now decayed remnants of silk tell a special tale of America's most

destructive conflict.

During the American Civil War, as in earlier conflicts, the flags of a combat unit (its

"colors") held a special significance. They had a spiritual value; they

embodied the very "soul" of the unit.

W. H. Druen of Rockville, Wisconsin, witnessed the attachment the men had to their colors

when he wrote home on August 1, 1861:

We are the color company of the Sixth Regiment, and carry the Regimental

colors; and I feel safe in saying in behalf Company 'C' that the splendid flag entrusted

to our care, shall not be dishonored by an act of ours. We shall bring it back

unsullied by traitors' hands.

Indeed, the loss of its colors in combat could seriously

jeopardize the morale of that unit. After the regimental color of the Sixth

Wisconsin briefly fell into the hands of the Eightieth New York at the battle of Antietam,

Lieutenant-Colonel Edward S. Bragg felt it necessary to explain... that the

regiment conducted itself during the fight so as to fully sustain its previous reputation;

that it did not abandon its colors on the field; that every color-bearer and every member

of the guard was disabled and compelled to leave; that the State color fell into other

keeping, temporarily, in rear of the regiment, because its bearer had fallen; but it was

immediately reclaimed, and under its folds, few but undaunted, the regiment rallied to the

support of the battery. The color lance of the National color is pierced with five balls,

and both colors bear multitudes of testimony that they were in the thickest of the fight.

But beyond these transcendental factors, flags served at

least three practical purposes on the nineteenth-century battlefield.

At the beginning of the Civil War, colorful uniforms were

adopted or adapted from pre-war militia service by the belligerents of both sides to

enhance unit morale or state pride. Such uniforms were not always conducive to

distinguishing friend from foe. Indeed, the Second Wisconsin, outfitted by Wisconsin in

gray uniforms, found itself under fire from both friend and foe during the first battle of

Bull Run! The thick gray-white smoke that clung near the ground on battlefields of the

black-powder era further complicated the problem. In such circumstances, flags were often

the only means of distinguishing the identity of the combatants. Unit flags also served as

the focal point for maintaining

alignment within the unit during an era when linear tactics predominated. The

single-shot,

muzzle-loading musket dictated that infantry fight in closely formed, standing lines of

battle to achieve effective concentration of fire. In spite of the revolution caused by

the adoption of the rifle-musket, which increased the effective range of a regiment from

seventy-five yards to well over 250 yards, the battles of 1861 and early 1862 were largely

fought with the smoothbore muskets of earlier periods, and officers were trained to handle

their men accordingly. Volley fire (necessitated by the inherent inaccuracy of the

smoothbore musket) demanded strict attention to proper alignment of all segments of a

military unit, lest a portion of the unit's fire fall harmlessly short. The unit's colors,

situated in the center of the firing line, provided the focal point by which company

commanders aligned their formations within the unit before firing.

"Guiding upon the colors" remained an important command even after the

rifle-musket drastically altered the necessity for strict lineal alignment. Lastly, flags

served as the focus for leading an assault or for rallying a broken unit. Where the colors

went, the men followed. Describing his part at Antietam after he had recovered the unit's

state flag, Major Rufus R. Dawes of the Sixth Wisconsin recollected:

At the bottom of the hill I took the blue color of the State of

Wisconsin, and waving it, called a rally of Wisconsin men. Two hundred men gathered around

the flag of the Badger state. . . .

I commanded 'Right face, forward march,' and started head with the colors in my hand into

the open field, the men following.

And, where the colors went, men usually died.

Because the colors drew an inordinate share of enemy

fire and were the object of capture, the color-party of the period was large and more than

ceremonial. The national color was carried by a sergeant, while the regimental or state

color was carried by a corporal. Anywhere from four to seven other corporals were selected

to form the color-guard (2)

whose sole duty in combat consisted of protecting the unit's flags. Only after the flag

was removed from a functional combat role did military tacticians reduce the size of the

color-guard.

2 U.S. War Department, U.S. Infantry Tactics,

for the Instruction, Exercise, and Maneuvers of the United States

Infantry, Including Infantry of the Line, Light Infantry, and Riflemen... (Philadelphia,

1861), 10-11.

Originally translated from the French in 1855 by then Major William J. Hardee, this same

plan of organizing

the nine-man color party was incorporated into the tactical manuals of Silas Casey (1862),

Henry Coppee (1862),

William Gilham (1861), the Confederate edition of William J. Hardee (I861), and H. B.

Wilson (I862). The

six-man or optional nine-man color-party had been regulation from 1835 through 1855 when

supplanted by

Hardee's tactics. Nevertheless,the out dated infantry Tactics,or Rules for the

Exercise and Maneuvers of the

United States Infantry was reprinted in New York in both 1858 and 1861 under the deceptive

guise of being a

"new edition," and was extensively used. Similarly, Captain S. Cooper's

1836 synopsis of this older tactical

system was reprinted under Captain M. Knowleton's deceptively titled Authorized Tactics,

U.S.A., including

Cooper's paragraph on the six-man color-party verbatim.

The importance of flags to military units during the

mid-nineteenth century was not limited to the military tacticians who prepared the drill

manuals that officers studied for the rudiments of marching and maneuvers. Patriotic

groups and individuals throughout the country answered Lincoln's initial call to arms by

presenting flags to the militia and volunteer companies that answered. Loyal Wisconsinites

were no different than their compatriots throughout the North.

Wisconsin's quota under Lincoln's initial call was for but

a single infantry regiment of ten companies.

Ten pre-war militia companies quickly volunteered their services for three months'

service, filled their ranks with recruits, and gathered at the old fair grounds in

Milwaukee to be equipped by the state.

One item the state did not provide the First Wisconsin Active Militia was a flag. The

nimble fingers of the patriotic ladies of Milwaukee quickly fashioned silk into a fine

national flag decorated with thirty-four silver stars, and on May 8, 1861, Governor

Alexander Randall traveled to Milwaukee to officially present the flag to the regiment on

behalf of the ladies. The Horicon Guards, Company C of the First Wisconsin, also received

an elegant silk national flag bearing a painted American eagle in

its canton, a gift of the ladies of Horicon. Like most of the company flags presented to

departing local units in 1861, that of the Horicon Guards never saw combat.

The enthusiasm that led to the formation of' the First

Wisconsin Active Militia brought offers for service from far more companies than there

were positions available. Although Washington did not authorize it, Governor Randall

organized the overflow into a second regiment of "State Active Militia" for

three months service and established its rendezvous at Madison. The militia companies

volunteering for this Second Regiment soon flocked to Camp Randall, many encumbered with

flags that had been presented by the communities whence they had departed.

Presentation color of the Miners Guard,

Company I, Second Wisconsin Infantry, 1861. Line drawing by, Robert D. Needham.

The La Crosse Light Guards (Company B of the Second

Regiment) arrived with a "white silk flag, with blue fringe and inscribed on an oval

ground in the centre: 'Presented by the ladies of La Crosse, July 4th, 1860, to the La

Crosse Light Guards.' " The Portage Light Guards (Company G) arrived with a silk

national flag presented by the ladies of the city prior to the company's departure. Both

companies arrived in the predominately gray uniforms adopted prior to hostilities.

Janesville Volunteers (Company D) arrived without uniforms, but boasted "a superb

national flag of silk" carried by Ensign Dana D. Dodge. Similarly, the Miners Guard

(Company I) arrived only partly uniformed. Nevertheless, the ladies of Mineral Point had

completed a "handsome merino United States flag" presented by G. W. Cobb before

the company departed on its stormy ride to Madison

in open wagons.

The most impressive flag, however, was that brought to

Camp Randall by the Belle City Rifles (Company F). The young ladies of Racine had

presented a color to this company in impressive ceremonies at Titus Hall prior to its

departure. The local newspapers described it in some detail:

It is of dark blue silk, with a silver fringe, On one side is painted a shield

inscribe 'Racine,

1861' with a national flag draped on either side of it, surmounted by an eagle holding the

bolts of Jove. Over is the motto 'Remember Sumter,' and on scrolls near the centre, 'For

Freedom,' and 'For God.' On the reverse is a shield with a star, surrounded by military

emblems, with the name of the company inscribed.

The flag was attached to a staff bearing a spearpoint and adorned with a set of

"heavy cord and tassels."

ONCE the regiment had assembled at Camp

Randall, there was little use for these patriotic company gifts. In the absence of

regimental colors, the colonel may have occasionally selected one or two of the company

colors to accompany regimental drill, and they undoubtedly decorated the tents of the

respective captains. The drill manuals and the Army Regulations, however, permitted only

one set of colors per regiment, and the company flags were accordingly relegated to the

captains baggage.

The Revised United States, Army

Regulations of 1861 ordained that each infantry regiment was to have a set

of colors consisting of two flags. Each was supposed to measure seventy-two inches on its

hoist (staff) by seventy-eight inches on its fly. The national color of this pair was

loosely described as conforming to the design specified for the large (twenty by

thirty-six foot) garrison flag. In the description of the garrison flag, the canton (the

section of blue in the upper staff corner which encloses the stars) was specified to

extend from the top through the seventh stripe and form the staff to a distance equal to

one-third of the length of the flag. On the garrison flag, these proportions resulted in a

canton that was nearly twelve feet square.

However, when compressed into the nearly square proportions of the national color, the

result was a canton that was decidedly rectangular - technically thirty-nine inches on the

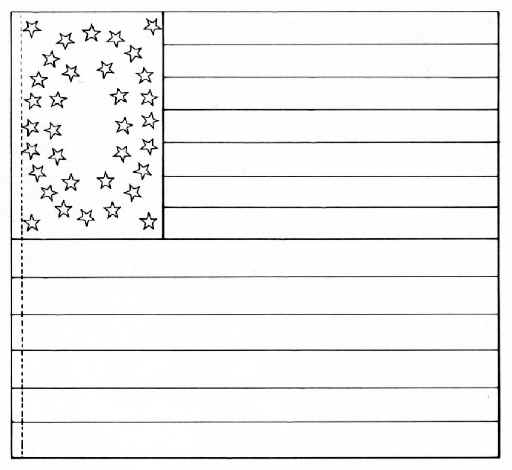

staff by only twenty-six inches on the fly. (3) The national color secured by the state for the Second Wisconsin conformed to

this literal interpretation of the regulations, though shortages in the overall

measurements of the flag resulted in a canton only thirty-two and a half inches on the

staff by twenty-three and a half inches on the fly.

3. U.S. War Department, Revised United States

Army Regulations of l861... (Washington, 1863), 461, paragraphs 1464 and 1466. This

description was copied unchanged from the similar regulations printed in 1841, 1847, 1857,

and 1861 (unversed). Although several contractors to the New York Quartermaster's

department depot consistently provided national colors with square cantons during the

Civil War, the literal oversight was not corrected until 1884, when the width of the

canton on the fly was officially specified as thirty-one inches on national colors.

Colonel S. Park Coon, commander of the Second

Wisconsin, did not trust the patriotic fervor that had furnished the First Wisconsin and

so many of the volunteer companies with colors during the first few months of the war.

Instead, on June 7, 1861, he assigned a nebulous "Captain Sanders" to he task of

providing colors for the Second and asked the state's quartermaster-general for

cooperation in the venture. Three Madison business concerns furnished all that Sanders

would require for the Second's national color. By June 19 he had obtained a staff for the

color from Church and Hawley for $8. On the next day an oilcloth cover to protect the flag

when furled and a belt with a carrying socket for the color-bearer were purchased from

Thomas Chynoweth, for $2.25 and $1.50 respectively. The more significant work, however,

was delegated to Mrs. R. C. Powers, who secured the necessary materials ($5.38 for silk,

$1.25 for a silk cord to secure the flag to its staff,

and 25@ for brass rings through which the cord passed), cut and sewed the material (for

$12), and gilded the stars and lettering upon the flag (for $7). She was paid on June 21,

and for $37.23 the Second Wisconsin had obtained a commendable color, in only three weeks'

time. (4)

4. Wisconsin National Guard,

Quartermaster Corps, General Correspondence of the Quartermaster General

(Record Group 1 159), Box 2 June 6 -10, 1861), letter of Colonel S. Patrick Coon to

Quartermaster-General W. W. Tredway, June 7, 186 1, Wisconsin State Archives.

Here-in after references to record Group 1 159 are cited as Wis. QMG, Gen. Corr.

The only individual of the

Second with the name approximating "Captain Sanders" was Sergeant (later

Lieutenant) George F. Saunders

of Company D. The respective bills of Church & Hawley of June 20, 186 1, Thomas

Chynoweth of the same date, and Mrs. R. C.Powers of June 21, 1861 may be found in Box 2

June 20-25, 1861).

If the flag had any shortcomings, it was its size, which was approximately six inches

short of regulations in both height and fly. The gilding performed by Mrs. Powers,

however, not only conformed to contemporary standards, but even exceeded usual practices

to permit the unit designation, "2ND REGT WISCONSIN

VOL" to appear properly on both sides of the center stripe. (Although regulations

called for embroidery, in actual practice the U.S. Quartermaster Department consistently

substituted painting or gilding for embroidery in the colors it caused to be made for the

Army between 1808 and 1880. Due to bleeding of the oil paints, it was usually impractical

to paint lettering on both sides of the same piece of silk.) The same gilding that Mrs.

Powers used for the unit designation was employed to apply the thirty-four stars to each

side of the double-thick, dark blue

canton. Lacking specifications, Mrs. Powers opted for a relatively simple star

arrangement of seven horizontal rows of equally spaced stars. Each row had five stars,

except the uppermost, which had four. Alignment with the lower stars was maintained by

simply leaving a gap above the vertical row closest to the staff.

Although the flag was provided with cords and tassels, the

requirement that its edges be fringed was neglected. There is evidence that the desired

fringe was not available in Madison. As it was the flag was completed only hours before

the Second Wisconsin entrained for Washington, precluding even a brief presentation

ceremony.

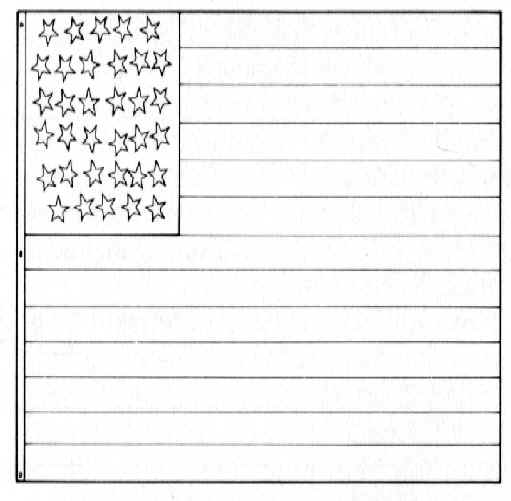

National color of the Second Wisconsin

Infantry, 1861-63

The Second Wisconsin Active Militia had been called to its

Madison rendezvous on April 23, 1861.

On May 6, the War Department advised Governor Randall that the Second would be accepted

under new quotas if it volunteered for three years rather than the initially anticipated

three months. Nearly all of the assembled companies acceded to the new conditions, and on

June 20 the Second Wisconsin Infantry departed Madison with its barely completed national

flag in the hands of the Randall Guards (Company H). Upon reaching the "seat of the

war" in northern Virginia, the Second was assigned to a polyglot brigade under the

command of Brigadier General William T. Sherman. Within the month,

Sherman's Brigade was marching towards a confrontation with the Confederate army near- a

creek called Bull Run. There the Second would nearly lose its month-old color.

IN the battle of Bull Run, Sherman's

brigade was committed piecemeal. In the confusion, the Second Wisconsin (clad in gray

uniforms) was fired upon from both front and rear, causing the regiment to retreat

hastily. The Second was rallied near a field hospital. While attempting to reform, the

color-sergeant of' the Second took time to assist acting corporal George L. Hyde, who had

been wounded, to the hospital. Private Robert S. Stephenson held the national color

for the color-sergeant during his absence.

Before the regiment had fully reformed, an

ill-advised order caused the Second to break again, this time in a panic for Washington.

While retreating, Stephenson was beset by elements of confederate cavalry. An

intervening fence offered temporary haven. Rescue came, however, when two of the

regimental bandsmen, Richard Carter and his brother George B. Carter, discarded their

instruments for muskets and succeeded in uniting approximately fifteen Union soldiers

around the threatened color. (5) Thus guarded, Stephenson and the color safely retreated.

5 "The Colors of the Second Regiment/The

Retreat." published in the Milwaukee Sentinel, August 9, 1861.

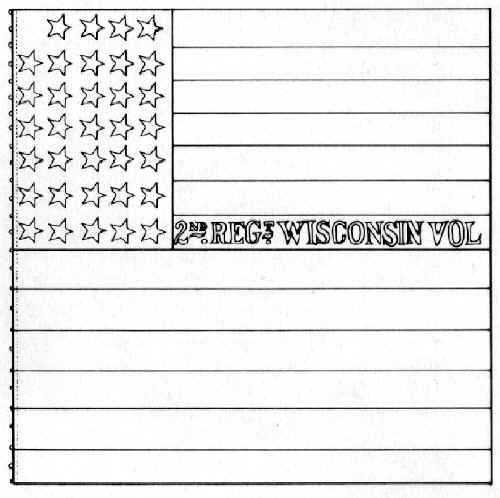

Regimental color of the Second Wisconsin

Infantry 1861-1863 (obverse).

Regimental color of the Second Wisconsin

Infantry, 1861-1863 (reverse).

While the Second Wisconsin was recuperating from its

losses at Bull Run, another flag was being prepared for it in Madison: its blue regimental

color. This new flag was unique to the early Wisconsin regiments. Composed of two layers

of dark blue silk, the new flag was bound on three sides with a heavy gold fringe. In full

accord with regulations, the obverse (the side viewed when the staff is to the viewer's

left) bore a nearly exact representation of the Great Seal of the United States, painted

in gold and browns, and copied directly front the 1861 Army Regulations. (6) A crimson-edged gold scroll

beneath the seal bore the unit designation in white letters: "2ND REGT

WISCONSIN VOLUNTEERS."

The two layers of silk were necessary, for the reverse side bore an entirely different

design: the 1851 version of the seal of the state of Wisconsin. This seal, in full color

and apparently adapted from the engraving appearing on the governor's stationery, was

painted on an arced panel edged with a gold border. Surmounting the seal on a gold scroll

was the state motto, "FORWARD!" in crimson letters.

This use of the state seal on a field of blue as a flag preceded the official adoption of

the first state flag by nearly two years.

6 Revised United States Army Regulations of

1861 ...(Washington, 1863), 460. The only significant

difference was the shield on the eagle's breast, which bore only stripes (nineteen), but

no blue chief.

On August 2, 1861, Governor Randall visited the Second

Wisconsin and presented this new regimental flag to the regiment. Of the original nine-man

color-party, only two had survived to receive the new flag. Joining these two individuals

with the other replacements was Robert S. Stephenson (Stevenson). For saving the national

color of the regiment at Bull Run, Private Stephenson had been promoted to carry one of

the two colors of the Second. He continued in this capacity through the Second Bull Run

campaign of 1862. Convalescing at a field hospital at the beginning of the Maryland

campaign, Stephenson roused himself from his sick bed and rejoined the Second Wisconsin on

the

eve of the battle of Antietam. He asked to be reassigned once more to the colors;

permission was granted. On the night of September 17, his body, riddled by seven bullets,

was found next that of color-corporal George W. Holloway in the infamous Cornfield. The

post of greatest honor had proved to be a post of mortal danger, as other colorbearers of

the Iron Brigade would discover.

Prior to (and later as a result of) the attack upon Fort

Sumter, the Wisconsin legislature had adopted several measures to enhance the preparedness

of the state militia. One hundred thousand dollars was appropriated for uniforms and

equipage, and a war loan of twice that amount was eventually authorized.

On the basis of this legislation, Governor Randall called into state service four

regiments of infantry in addition to the First and Second regiments. Randall successfully

politicked to have all of these units accepted into federal service as three-year

volunteers, which permitted the state to recoup the money expended in equipping and

sustaining these regiments. And among the equipage of war that the state had purchased

were several colors, including those of the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers.

Presentation color

of the Sauk County Riflemen, Company A, Sixth Wisconsin Infantry, 1861.

The companies of the Sixth Wisconsin had been organizing

since April. As the Second Wisconsin prepared to depart Camp Randall, the companies of the

Fifth and Sixth regiments were called to rendezvous at the Second's former barracks. The

Sauk County Riflemen (soon to become Co. A of the Sixth) had completed their recruiting by

June 6. When the Sixth's Lieutenant-Colonel, Julius P. Atwood visited Baraboo to

officially swear the company into state service, the ladies of the town presented the

company with a small, silk United States flag bearing a painted eagle in its canton.

It would be the only recorded flag privately presented to the Sixth. For its regimental

colors, the Sixth would have to rely upon the graces of the state.

Possibly remembering the delay that had occurred between

the delivery of the Second Wisconsin's national and regimental colors, Wisconsin's

quartermaster-general, William W. Tredway, evidently sought a source that could deliver

regimental colors in a short period of time. Army Regulations nonchalantly described an

infantry regiment's "second, or regimental color, to be blue, with the

arms of the United States embroidered in silk on the centre. The name of the regiment in a

scroll, underneath the eagle." Given such a vague description, the only

complexity lay in the rendition of the arms of the United States, either in embroidery or

the traditional substitute, oil paint. Hence, on June 27,

1861, Quartermaster-General Tredway addressed a letter to S. F. White & Bro. of'

Chicago for two such regimental flags, substituting painting for embroidery. S. F. White

& Bro. responded two days later, quoting a price of $45 each if fringed and $40 if

not. Under no great pressure to provide colors for the Fifth and Sixth regiments, Tredway

apprised White on July 1 that the "colors will not be ordered at present. "

However, in Washington the situation began to look ominous as the three months' militia

and volunteers called for in April began to muster out. Suddenly the Lincoln

administration was again clamoring for troops, and General Tredway was forced to hurry the

outfitting of the two regiments at Camp Randall. Anticipating national colors through a

New York contract with Paton &

Co., Tredway concentrated on securing regimental colors for the two Madison units. On July

8, therefore, Tredway placed the following order with S. F. White & Bro.

Please have two stand of colors made immediately for 5th and 6th Regiments

Wisconsin

Volunteers (one each). They must be made in accordance with the printed regulation

No. 1370 page 436 (Army Regulations 1857) for infantry Regimental color, blue silk,

fringe, cord & tassels & pike, all complete, and forwarded to me at this

place. At one time I supposed I should not need them & so wrote you, but they

are now wanted if you I n furnish them as you then stated.

Three days later Tredway forwarded S. F. White an

order for six and a half yards of flag fringe and badgered White to know when the

colors would be completed. White, however, was not a flag manufacturer, and he had let out

the work to Gilbert Hubbard & Co., also of Chicago. Gilbert Hubbard & Co. acted

swiftly on the order, and by July 16 had shipped the two flags via express to Madison.

(7) Two days later, the Sixth

Wisconsin was drawn up for review in their newly issued gray uniforms, and the blue

regimental color was entrusted by Colonel Lysander Cutler to Sergeant George W. Reed of

Company G. (8)

7. WiS. QMG, Gen. Corr., Box 4 (July

23-25,1861), Gilbert Hubbard & Co. to Q. M. Gen. W. W. Tredway,

July 25, 186 1. Gilbert Hubbard & Co.'s bill of July 23, 186 1, is in the same folder.

This bill was returned for

proper signatures and finally for correction when it was discovered that the price failed

to meet the quote of

S. F. White & Bro. See S. F. White & Bro. to W. W. Tredway, June 29, 1861,

Box 3 June 26-30, 1861);

Gilbert Hubbard & Co. to H. K. Lawrence, July 27, 1861, Box 4 July 26-28, 1861); and

Gilbert Hubbard & Co.

to H. K. Lawrence, July 31, 1861, Box 4 (July 29-31, 1861), and Wis. QMG, Letter

Books, Vol. 1, pp. 464, 482,

and 502. 8 Diary of Sergeant Levi B. Raymond, Company G, Sixth Wisconsin, for 186 1, entry

of July 18

(manuscript in private collection, Des Moines, Iowa). George W. Reed was furloughed

in February of 1862 to

attend his dying child. When he failed to return he was declared a deserter, effective

April 14, 1862; see

Raymond diary for 1862, entries of February 18, 19, 22, and 23. In addition to

Sergeant Reed, five others were

assigned to the colors at Camp Randall: Corporal Mamory V. Smith (Company B),Corporal

Mathew Keogh

(Company D), Corporal Andrew G. Deacon (Company E), Corporal Hirman B. Merchant (Company

H), and

Corporal William A. Remington (Company K). See CWV, Vol. 1, p. 235; (General

OrdersNo. 5, Sixth Regiment Wisconsin Active Militia, July 12, 1861. See also p. 236 of

the same volume.

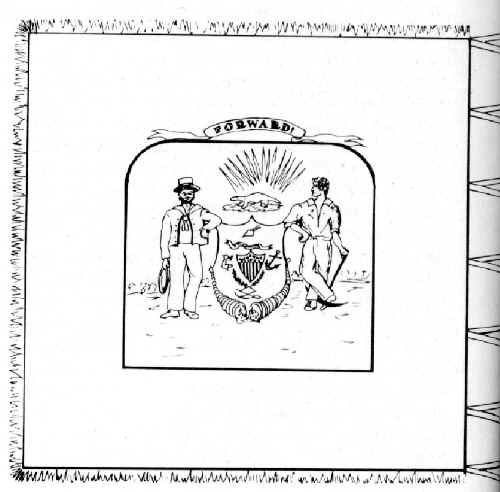

Regimental color of the Sixth Wisconsin

Infantry, 1861-1863.

Composed of a single layer of pieced, dark blue

silk, the regimental color of the Sixth Wisconsin was fringed in yellow on three sides.

(9) On each side, the artist for

Gilbert Hubbard & Co. had executed in oils a full-color rendition of the seal of the

United States - the eagle predominantly in brown tones and grays, the shield in red and

white stripes under the blue chief and bordered in gold, the arrows in gold and the laurel

in green in opposing talons, the sky behind the eagle's head a sunburst fading to a

gray-blue sky studded with white stars and surmounted by a purple and gray cloud. From the

eagle's beak flowed a red scroll bearing the motto "E PLURIBUS UNUM" in black

letters. A simple light-red scroll, edged with gold, bore the gilded lettering "6TH

WISCONSIN REGIMENT" in an arc below the seal and completed the painted designs. What

model may have served as the artistic basis for this rendition of the U.S. seal is

enigmatic, as a multitude of variations had found their way into print by the middle of

the nineteenth century. Clearly the artist was not influenced by the stiff, unnatural

eagle

depicted in Army Regulations. His interpretation of the bird on the regimental color of

the Sixth Wisconsin, and on other early colors purchased from Gilbert Hubbad & Co. in

1861 and early 1862, was far more relaxed and lifelike. (10)

9 The flag measures sixty-eight inches on its

staff by seventy-five inches on its fly, exclusive of the

three-inch-deep silk fringe bordering three of its sides.

10 WiS. QMG, Letter Books, Vol. 2, pp. 232, 266, and 650, and Vol. 4, p. 14.

Between September 26, 1861, and April 4, 1862, Wisconsin's Quartermaster-General ordered

sets of colors from Gilbert Hubbard & Co. for the reorganized First and the Ninth,

Tenth, Eleventh,Twelfth, Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Sixteenth,

Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth regiments. All were basically of the same

pattern, although the artist who executed the eagle on the colors of the Fifteenth

executed it in a more heraldic form. All these regimental colors bore the motto

"FORWARD" upon them.

ON July 28, 1861, just four days after

the Fifth Wisconsin had departed for Washington, the Sixth Wisconsin followed her sister

regiment. The Sixth left with but a single flag, the blue regimental color presented by

the state ten days earlier. The national color had failed to materialize. However, with

the organization and equipage of the Seventh and Eighth regiments, the state would rectify

its failure to furnish that national color.

On July 23, 1861, the U.S. War Department authorized

Wisconsin to complete the organization of the two additional active militia regiments that

the Wisconsin Legislature had established at Governor Randall's urging. Although the

governor had not planned to call the Seventh and Eighth regiments into camp until after

the fall harvest, the Union defeat at the battle of Wilson's Creek in Missouri prompted

the War Department to press Governor Randall for an earlier rendezvous. Wisconsin's

Quartermaster-General therefore began to arrange for the equipping of these two new units.

On August 20, 1861, an order was confirmed with Gilbert Hubbard & Co. that provided

flags not only for the two new regiments, but also for the Sixth regiment's lack of a

national standard as well. Deputy Quartermaster-General Means's order was succinct,

stating in part: (11)

Please send us at as early a day as

possible one Regimental color (blue Silk) for 8th Regm't Wis. Vol., army regulation in all

respects.

And three national Colors, Silk, regulation size, 6 ft. 6 in. by 6 ft., marked on the

middle stripe as following:

One of them - 6th Regt. W. V.

7th Regt. W. V.

8th Regt. W. V.

The last two with staff, spearhead, cords & tassels; 6th Regm't col. all compl. except

staff. . . .

11 The national colors of' the Seventh and Eighth

regiments had previously been ordered on

August 8 by Assistant Quartermaster-General H. K. Lawrence. The bill for these flags

amounted to $198 ($50 for the complete regimental flag of the Eighth, $45 each for the

national colors of the Seventh and Eighth reg iments, and $40 for the national flag of

tire Sixth without pole or tassels). An additional $18 was charged for

lettering the three national colors; see Wis.

QMG, Gen. Corr., Box 5 (August 1-5, 186 1), bill of Gilbert Hubbard & Co.

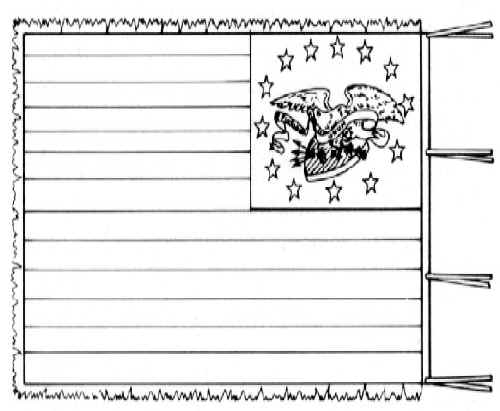

National Color of the Sixth Wisconsin

Infantry, 1861-1863.

Apparently these flags were delivered by the sixth of

September. Rather than ship the national color of the Sixth via express, General Tredway

devised a less expensive shipping procedure.

On September 16, he informed Colonel Cutler of the Sixth Wisconsin:

"I send per hands of Qr. Master H.P. Clinton of 7th Wis. Reg. your

National color.

You can have them mounted in Washington & this department will pay the bill upon

presentation."

A closing note informed Colonel Cutler that the Seventh would depart in two days.

The national colors provided by Gilbert Hubbard

& Co. under Means's order conformed to the regulations with but a single deviation:

the use of gold paint where silver embroidery was officially specified. This gilding was

used in both the application of the unit name, "6TH REGT WISCONSIN

VOLUNTEERS.", to the center stripe and the thirty-four stars in the canton. These

gold stars were arranged into six horizontal rows, the topmost and the bottom rows

containing five stars each, the four center rows six stars each. Like the regimental

colors provided by Gilbert Hubbard & Co. up to this time, the flag was secured to its

staff by means of silk ties that passed through four small brass

grommets equally spaced in the hemmed leading edge of the flag. (12) So,

like the Second Wisconsin, the Sixth was a belated recipient of it's full complement of

colors.

12 From the surviving fragments, the flag appears to

have measured seventy-one inches on its staff by at least

seventy-two inches on the fly, exclusive of the four-inch- deep buff silk fringe. The

canton measured thirty-eight inches on the staff by twenty-four inches on the fly. Only

"VO" of VOLUNTEERS remains on the center stripe.

In placing the order with Gilbert Hubbard & Co.

on August 20, 1861, for the colors required for the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth regiments,

no mention was made Regimental color for the Seventh Wisconsin. For reasons not clear, the

state had decided to have that flag made in Madison. On August 1, 1861, a voucher was

issued to Mrs. R. Powers of Madison for one "Regimental color" and the

"Silk & Trimmings for Regimental color for 7th Reg't." Audited twenty days

later, Mrs. Powers' payment included $15.00 for actual sewing of the flag, $20.00 for the

painting on the color, and $19.61 for "Silk & trimmings for same." The last

amount did not include the six and a half yards of fringe or the cords and tassels. These

had been ordered from S. F. White & Bro. of Chicago on July I 1, but

they had not been received by August 1. As with earlier flag orders, S. F. White &

Bro. had subcontracted the order to Gilbert Hubbard & Co., who finally delivered the

yellow silk fringe and the blue and white cords and tassels on August 6. The completed

flag was issued to Quartermaster Henry P. Clinton of the Seventh during the last week of

September. (13)

13 The Return of Property Purchased and Issued

by the Quartermaster-General for the Year Ending August 1, 1862, cited above (Record Group

1163), Abstract A, indicates a receipt date of september 28, but Abstract E lists an issue

date of September 21. The latter date is undoubtedly correct, since the Seventh departed

Madison on that date.

Regimental color of the Seventh Wisconsin

Infantry 1861-1863.

National color of the Seventh Wisconsin in

Infantry, 1862-1863.

Although conforming to the vague specifications of

Army Regulations, the painted U.S. seal and the scroll beneath it on the regimental color

of the Seventh were unlike any design heretofore provided by either Gilbert Hubbard &

Co. or any of the other suppliers of flags to Wisconsin during the Civil War.

In lieu of the traditional frontal view of a shielded eagle with upright, extended wings,

the regimental color of the Seventh depicted a side view of a crouched eagle with partly

folded wings. Moreover, rather than supporting the shield on its breast, the gold and

brown eagle was perched upon the shield (which had the additional irregularity of

having white stars upon the blue chief). A gold scroll, edged red along its upper border

but blue on the lower portion, emanated from the eagle's beak, bearing the national motto

in black lettering. A panoply of flags (including the U.S. flag) protruded from behind the

eagle's lowered, golden head, all surmounted by nineteen scattered, silver stars. Although

distinctive, the design was not unique. Rather it was copied (with the minor modification

of the scroll) from a popular motif that had been utilized on several contemporary printed

objects, including at least one widely distributed guide to commercial signal flags.

(14) Beneath these devices the artist

had painted a curling white and red rococo scroll bearing the unit's name abbreviated in

gilt figures and letters, shadowed red, low and to the viewer's right. (15) Although much of the paint has flaked off, it

is not so nearly damaged as its matching national color.

14 Henry J. Rogers, Rogers American Code of Marine

Signals ... (Baltimore, 1855), title page.

15 The color, exclusive of the two-and-a-half'-inch-(heel) yellow silk fringe, measures

sixty-nine and

three-quarters on its staff by seventy-one and a half inches on its fly.

The painting, applied identically to each side of the single layer of dark blue silk, has

mostly flaked away.

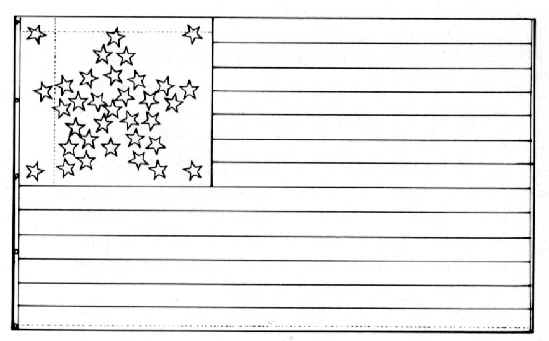

Originally believed to be of regulation size, no

more than two-thirds of the national color of the Seventh Wisconsin survives. Any

fringe it may have had has been torn away. The canton, which originally bore

thirty-four gold stars (thirty set in a double ellipse - probably ten in an inner ring

surrounded by twenty in a concentric outer ring - with one other star set in each corner

of the canton) is badly damaged. (16) Surprisingly, no evidence of a unit abbreviation appears on the center stripe or

any of the other surviving fragments. (17) The star pattern (so different from those upon the national flags of the Sixth

and Eighth regiments ordered August 20, 1861) as well as the absence of any painted unit

abbreviation indicates that the national flag of the Seventh carried from at least

mid-1862 until November of 1863 was not the color ordered from Gilbert Hubbard & Co.

and delivered on September 5, 1861, with the regimental color of the latter. Instead, the

flag exhibits the characteristics of several eastern flag manufacturers who served the

Philadelphia U.S. Quartermaster's Depot and several eastern states.

16 As an alternative star pattern, the inner ring may

have had only nine stars, with a corresponding gap at the

top or bottom of the ring; in that case the thirty-fourth star graced the center of the

canton.

17 The surviving fragments measure approximately seventy-one and a half inches on the

staff by fifty-five (of the presumed seventy-eight) inches on the fly, inclusive of the

two-inch-diameter sleeve that held the flag to its

original staff. The canton measures thirty-six inches on the staff by twenty-four

inches on the fly, and the stars that remain each are two and a half inches across their

points.

SINCE it is convincingly

established that the pair of colors secured for the Third Wisconsin was purchased by

Colonel Charles S. Hamilton in Philadelphia (18), all a strong possibility exists that the Seventh may have turned to the

Philadelphia market for a new color in early 1862.

Did Colonel Joseph Van Dor of the Seventh take the original national color home with him

as a souvenir when he resigned on January 30, 1862? Documentary evidence strongly

indicates that the Seventh had two colors when it left Madison in 1861.

18 The colors of the Third Wisconsin exhibit the same

artistic characteristics as those furnished the

Regular Army prior to the Civil War. The painting of the colors for the Regular Army

had regularly

been subcontracted to Samuel Brewer of Philadelphia prior to hostilities.

On September 17, 1861, the state's Military Store Keeper

recorded the receipt of two "Belts for Color Bearers"

for the Seventh regiment. These belts had been ordered on the sixteenth from Thomas

Chynoweth of Madison at the cost of $4 by Assistant Quartermaster N. B. Van Slyke.

These two belts were issued to the Seventh upon a requisition, dated September 19, that

also included "1 sett Regimental Colors" and "1 staff & Trimmings for

U.S. colors."

The set of regimental colors referred to was that furnished by Mrs. Powers of Madison.

This staff for "U.S. colors" is enigmatic. Although firm documentation is

lacking, it was probably procured from Church & Hawley of Madison, who consistently

supplied the state with marker poles and who had furnished the Fifth regiment with a

"large Flag Staff" for $6 in July for its national color. Additional expenses

relating to the staff for "U.S. colors" included $1 for plating the mountings

and $2.50 for cords and tassels. Since Gilbert Hubbard & Co. had already provided a

set of the latter on August 6 for the regimental color made by Mrs. Powers for the Seventh

Wisconsin, and since the national color sent to the state on September 16 by the same firm

for the Seventh was billed as "all complete with fringe, Pole &c.," the flag

staff requisitioned on September 19 was apparently for some other flag. And, though a

faint possibility exists that the staff and its trimmings may have been for the national

color that the Seventh carried to Washington for the Sixth regiment, the dating of the

bills and their continued association to the Seventh regiment strongly suggest that it was

for some other U.S. flag of the Seventh,

possibly a presentation color.

After the Seventh Wisconsin entrained for the East on

September 21, a brief stop was made at Stoughton, home of the Stoughton Light Guard, the

Seventh's Company D. The state papers reported that the ladies of that town "had made

a fine banner to present to the Stoughton company, but finding that under the regulations

it would be only an encumbrance if carried, did not present it.

On the other hand, this had not deterred the Grand Rapids

Union Guards (Company G)

from bringing along the national flag that had been presented to them. By inference, there

clearly was no need for another national flag in the Seventh Wisconsin when it departed

Madison.

Nevertheless, when the Seventh joined Brigadier-General Rufus King's Brigade near

Washington on October 1, 1861, a soldier of the Sixth Wisconsin would record:

"The 7th Wisconsin arrived here last Tuesday. Our boys and those of the

2d made extravagant demonstrations of delight when they saw the Grey uniforms and blue

flag coming up the road from towards Washington ...."

What had become of the Seventh's national color? In view of the real danger of being

fired upon by Union forces because of their gray uniforms, it seems incredible that the

Seventh would have gone to war without it. But the reason for its absence, like the flag

itself, is lost to history.

Presentation color of the grand Rapids

Union Guards, Company G, Seventh Wisconsin Infantry, 1861

UNDER these six colors, the Wisconsin contingents of the Iron Brigade

would fight their first major engagement together at Gainesville (more recently called the

battle of Brawner Farm), cover the retreating Army of Virginia at Second Bull Run, storm

Turner's Gap at South Mountain, and capture and lose the Cornfield at Antietam on the

bloodiest single day of the war. With the addition of the Twenty-fourth Michigan, they

would protect the Army of the Potomac's flank at Fredericksburg, brave the Confederate

sharpshooters at Fitz Hugh's Crossing, and skirmish at Chancellorville. The flags would be

torn by musketry and shell fragments, the staffs scarred by well-aimed bullets. By 1863,

battle and the elements had reduced the flags of the Iron Brigade to tatters. Of course,

the problem was not restricted to the flags of the Iron Brigade. By the middle of the war,

the flags that the state had purchased in 1861 for other Wisconsin volunteers were also in

need of replacing.

For example, at the battle of Perryville, Kentucky (also

called the battle of Chaplin Hills by the Union participants), on October 8, 1862, the

First Wisconsin Infantry suffered staggering casualties protecting the left flank of the

Union Army of the Ohio from wave upon wave of Confederate assaults. The colors of

the First were riddled, and its staff was struck twice. Of the color-party, only three

were unscathed when night ended the battle. When the color-sergeant fell, grievously

wounded, a private, James S. Durham of' Company F, grasped the flag and kept it aloft.

Despite its losses, at one point the First

Wisconsin counterattacked, capturing the battleflag of the First Tennessee Volunteers and

dragging the abandoned guns of the Fourth Indiana Battery to safety. In appreciation of

these actions, the Indiana artillerymen presented the First Wisconsin with a set of colors

that included a new national and regimental color as well as a small marker. The receipt

of these new colors permitted the First Wisconsin to retire the battle-worn national color

it had received from the state in October of 1861.

On January 19, 1863, Colonel John C. Starkweather returned the First's national color to

Governor Edward Salomon with an eloquent letter of transmittal that was later published in

the Madison Journal.

Starkweather's account struck a chord in the patriotic

spirit of State Senator Benjamin F. Hopkins, a Republican representing Wisconsin's

Twenty-sixth Senatorial District. On February 16, 1863, Hopkins begged the

indulgence of the senate to suspend the rules in order to introduce a resolution

establishing a joint committee commissioned with the responsibility of establishing a

state flag and preparing legislation that would permit Wisconsin regiments to substitute

this new flag for their worn-out colors.

Hopkins' resolution carried both houses, and a five-man committee headed by Hopkins was

created to translate his recommendations into appropriate legislative form. The five-man

joint committee deliberated less than a month on the design for the state flag. On March

13, the committee reported the following proposal for the design of Wisconsin's state

flag:

To be of dark blue silk, with the arms of the State of Wisconsin painted or

embroidered in silk on the obverse side, and the arms of the United States, as described

in paragraph 1435, of 'New Army Regulations,' painted or embroidered in silk, on the

reverse side. The name of the regiment, when used as a regimental flag, to be in a scroll,

beneath the State arms.

The size of the regimental colors to be six feet six inches fly, and six feet deep on the

pike. The length of the pike for said colors, including spear and ferrule, to be 9 feet

and 10 inches. The fringe yellow; cords and tassels blue and white, silk intermixed.

This proposal was adopted by the senate on the sixteenth and by the assembly the next day.

On March 25, 1863, it officially became joint Resolution No. 4 of that year.

Next

page 1863-1865 |